Achebe and the book

We talked a little about Achebe's origins, that he was an Igbo who grew up in a cultural "crossroads": his father had joined the missionaries and accepted their education, while his great uncle rejected the missionaries. Growing up, Achebe moved between the two groups, but ultimately he was educated and became one of the modern, progressive young men of his time.

He wrote Things fall apart, partly at least, to present African life and experience from an African rather than a European perspective (such as Joseph Conrad's Heart of darkness). Achebe has said that he saw writing his novel as a "revolution" which could help his society recover from its sense of "denigration". He wrote the book in English, which was a controversial choice, and we briefly discussed the pros and cons. By writing in English, we thought, he appealed to a wider readership and perhaps to those he most wanted to reach, but not writing it in his own language could be seen to contribute to the debasement of his own culture.

We commented that while we hadn't read many African books, we had read Ben Okri's The famished road, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Half of a yellow sun. Adichie, like Achebe, is from the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria, while Ben Okri is Urhobo (though his mother was half-Igbo).

Our discussion

We all agreed that Achebe presents an interesting story of people's lives in an African (southeast Nigerian) village - a fascinating window into a world that's gone - but that it was clear that something else was going on underneath. We loved the small details about life in the village, such as the protagonist Okonkwo's compound and his three wives, each in their huts telling their stories to their children.

|

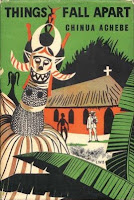

| First edition, Heinemann |

We discussed village life and customs, their gods, their food, and their cultural practices, some of which seemed cruel to our eyes (such as the abandonment of twins, the killing of an innocent person - here, Ikemefuna - as retribution for the sins of others). We noted that not all Igbo villages had the same practices, and that those in the village in which the novel is set, Umuofia, know this. However, it is each village's conventions, beliefs and practices that provide the glue that keeps them together and successful as a community.

We liked the rounded or realistic picture Achebe paints. Okonkwo is presented as the true "conservative", the person who accepts his people's traditions and is not prepared to think about or question them. He regularly ignores the advice of others, is described as “not a man of thought but of action”. However, his good friend Obeirika is more thoughtful. He generally accepts the traditions, but not without some thought and willingness to question them. He is not afraid to show a softer side. Achebe writes after one calamity befalls Okonkwo:

Obierika was a man who thought about things. When the will of the goddess had been done, he sat down in his obi and mourned his friend’s calamity. Why should a man suffer so grievously for an offence he had committed inadvertently? But although he thought for a long time he found no answer. He was merely led into greater complexities. He remembered his wife’s twin children, whom he had thrown away. What crime had they committed?

This brought us to the issue of the missionaries. How wrong were they we considered? Wasn't it reasonable to disapprove practices like abandoning twins or killing in retribution, was it wrong that they welcomed the clan's outcasts? We noted that, just as in Umuofian society where we see the contrasting behaviours and attitudes of Okonkwo and Obierika, there are different behaviours and attitudes among the missionaries and other white people. Mr Brown, for example, had an open, co-operative approach while his successor, Mr Smith, took a hard approach. Achebe writes:

Mr Brown’s successor was the Reverend James Smith, and he was a different kind of man. He condemned openly Mr Brown’s policy of compromise and accommodation. He saw things as black and white. And black was evil. He saw the world as a battlefield in which the children of light were locked in mortal conflict with the sons of darkness.

So, Achebe, in this book, is not uncritical of either side of the colonial equation, but we agreed that his final point in the novel makes clear his attitude to the colonial mindset. The title of the District Commissioner's planned book "The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger" euphemistically describes the colonials' mostly violent/aggressive subjugation of African people as "pacification", and demonstrates an arrogant assumption that a society not like their own is "primitive”.

We discussed the language a little too. We enjoyed the proverbs, the imagery, and the folk tales such as the one about the selfish tortoise.

Questions

A member shared some questions from the reading group guide at the back of her e-book. One asked about fate versus personal agency. We didn't discuss this at depth but felt that while Okonkwo started by believing he was in control of his life, that he could make himself a great man unlike his father, by the end he was feeling dogged by bad "chi". He ended up without a proper burial, just like his father.

Another question related to the novel's circularity. Most of us hadn't seen it that way, though we agreed that Okonkwo ending up without a proper burial just like his father could be seen as circular. We also discussed the linear aspect to the narrative, the building of calamities and events, and the use of parallels, such as rigid, conservative Okonkwo versus the thoughtful Obierika parallelling the black and white Reverend Smith versus the conciliatory Mr Brown.

No comments:

Post a Comment